The Diplomat (1989)

— David Gergen, political commentator

Watch this video clip from the documentary. As you watch the clip, ask yourself:

- How did Bush and Baker react to the news that the Berlin Wall had fallen?

- What diplomatic reasons did they have for reacting the way they did?

James Baker was sworn in as secretary of state at a particularly turbulent time in global politics. After the second World War 45 years earlier, the German nation had been split in two – East and West Germany. In the decades following the war, tensions grew between Western Bloc Nations (led by the United States) and Communist Eastern Bloc Nations (led by the former Soviet Union). The Cold War, as it became known, caused West and East Germany to be pulled in two different directions. Western Germany became an ally of the Western Bloc, while East Germany was considered a Soviet satellite.

Berlin, the largest city in East Germany, was also separated into East and West sections. Initially, the separation of Berlin offered East Germans an opportunity to circumvent their nation’s emigration restrictions; by going to West Berlin, East Germans could easily leave the Eastern Bloc for the West. But in 1961, East German officials erected a concrete barrier between the East and West portions of the city. That barrier, the Berlin Wall, stood for nearly 30 years.

When Baker took office, Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet General Secretary, was deep in a campaign to reform communism. Baker’s first order of business as secretary of state was to establish a relationship with Edourd Shevardnadze, the Soviet minister of foreign affairs and Baker’s counterpart. Baker invited Shevardnadze to Washington, and the two then flew together to Jackson Hole, Wyoming. During the flight, Baker focused on figuring out what Shevardnadze needed to make his country’s reforms successful. This approach to diplomacy – figuring out what his adversary wanted or needed – became a hallmark of Baker’s job style.

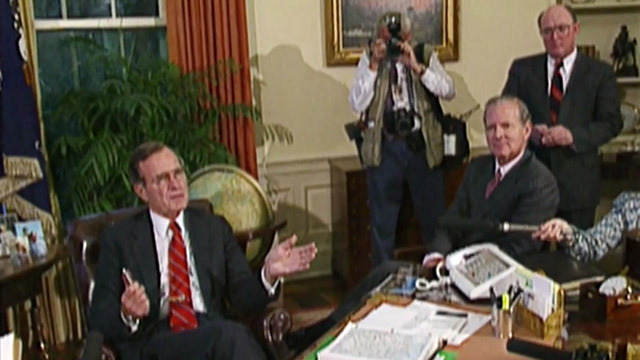

Two months following the trip to Jackson Hole, Baker’s relationship with Shevardnadze was put to the test when East Germany suddenly decided to open up the Berlin Wall. In short order, East Germans streamed into the West. The world celebrated, but Bush and Baker were measured in their response. The opening of East Germany represented a blow to the Soviet empire; Bush and Baker did not want to damage their fragile relationship with Gorbachev by gloating. Instead they downplayed the event to the press. Bush slumped at his desk while casually answering reporters’ questions about the fall of the Berlin Wall. The press criticized his nonchalance at the time, but it effectively sent a signal to Gorbachev that the U.S. was not going to take advantage of the situation. Gorbachev would later say, “I think it is important that the United States of America at that time pursued this particular course of understanding and interaction.”

The dramatic changes in Germany presented President Bush and Baker with an unexpected opportunity. For 40 years, the divided Germany was the epicenter of Cold War tensions. Now, with the Berlin Wall open, Baker and Bush saw a chance to help reunite the two Germanys – and to bring the newly unified Germany into NATO, the alliance of Western nations.

The political challenges of reuniting Germany were daunting. Leaders of France and England, Germany’s former enemies, were not pleased with the prospect of a giant new Germany. Bush and Baker needed to simultaneously assure the French and British leaders that Germany could be trusted, while also leaning on them to agree with the United States’ foreign policy directives.

Meanwhile, Gorbachev faced significant pressure back home. Losing East Germany to the West threatened to get the Soviet leader ousted. When it came to the Soviets, Baker and Bush set about doing what Baker did best: solving the other party’s problems in order to solve their own. Baker later explained: “It’s so important to understand the political constraints of the person across the table.”

Baker developed talking points to help Gorbachev with the hardliners back home. He emphasized that a stable, unified Germany within NATO would be better for the Soviets than a neutral Germany, which could act like a loose cannonball. Eventually, the Soviets came around. In May 1990, during a meeting in Washington, DC, Gorbachev agreed that the newly unified Germany should be allowed to enter NATO. By summer, Baker’s diplomacy had won over both the British and the French. Gorbachev signed the formal agreement to allow German reunification within NATO. It was a major diplomatic victory for Baker.

Baker had an advantage that few secretaries of states had enjoyed — a close personal relationship with the U.S. President.

Baker began his political role as secretary of state at a critical time in U.S. history.

Baker advised President Bush to not show too much emotion when reacting to the news of the fall of the Berlin Wall.